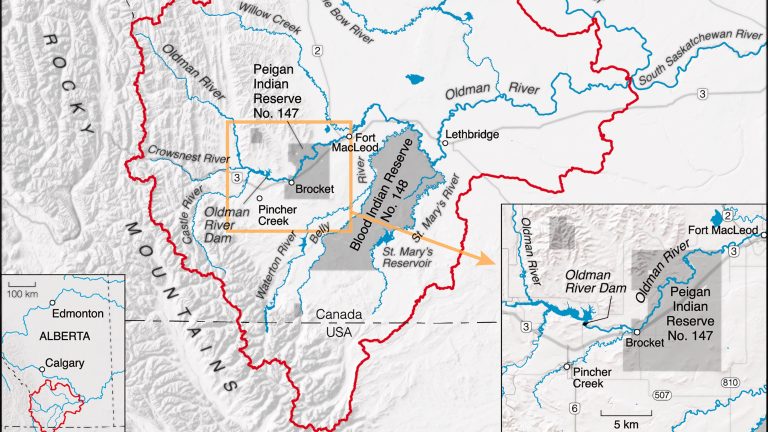

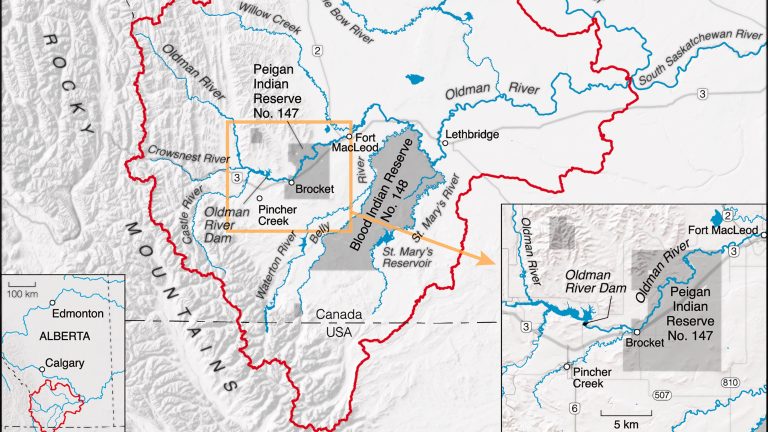

The Oldman River Dam is located east of the Rocky Mountains (Map by Eric Leinberger, 2022)

A new paper published by assistant professor Michael Fabris articulates the ways in which the instruments of the colonial state of Canada are incapable of adequately engaging with the laws and legal frameworks of Indigenous communities.

Published in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers, the paper examines the Piikani Nation’s efforts to challenge the Oldman River Dam, which was constructed in the 1980s, and the Environmental Assessment Review Process (EARP) that followed.

“This article argues that when looking at Indigenous opposition to resource extraction, it is not just about communities trying to use whatever tools of Canadian law are available to protect our lands and waters from the impacts of resource extraction. Rather, as I explore through analysis of Piikani interventions within the Oldman River Dam environmental assessment, Indigenous communities are often forced to find ways to creatively articulate our own spatial relationships with our waters and lands through the limited terms and frameworks that are available to us within settler colonial law.”

“By intervening within the EARP of the Oldman River Dam, Piikani members attempted to articulate Piikani relationships with the Oldman River on their own terms, expressing Blackfoot geographies in ways that did not necessarily correspond with either the inherent structure or specific terms of reference of the panel. Although the ORDEAP Final Report included some recommendations that supported the Piikani Nation’s position, ultimately the Panel reframed Piikani relationships with the water into its own concepts and grammar of “environmental and socio-economic impacts,” and explicitly denied attempts by Piikani to articulate their own understandings of water relationships, whether through inherent expressions of Piikani jurisdiction or through the assertion of treaty rights.”

By refusing to engage with Piikani legal frameworks, and instead reducing the discourse to that of “environmental and socio-economic impacts”, Fabris highlights that the EARP process “did not just implicitly prevent the articulation of Piikani relationships with the river, but explicitly advised against these expressions even being a matter of negotiation between the Piikani Nation and the province.”

This ultimately resulted in a settlement agreement which both “refused to define the nature of Piikani water rights, and required the Nation to agree not to make any attempts to assert or define these rights through court action or other means for the duration of the agreement.”

“The experience of the Piikani Nation with the ORDEAP, I argue, draws attention to the significant, if not outright inherent, limitations of asserting our own legal and geographic relationships to water within settler state IA assessments, even when strategically articulated through colonial interpretations of treaty rights.”