by Amy Thai, BSc Environmental Science (2005), MSc Geography (2007)

When we’re young and someone asks us, “So what do you want to be when you grow up?” it’s an easy answer. “A teacher!” “A doctor!” “An astronaut!” And maybe these days we’ll also hear, “A YouTuber!” When I graduated from university, I thought I wanted to go into “community-based environmental outreach”. I wanted to teach everyone how to be green and save the world. But I’ve now realized that what I want to be when I grow up is a moving target (as well as the definition of when we’ve “grown up”). Each job I’ve had has been a lesson in what I like and dislike when it comes to a career, and I’m still looking for that sweet spot.

Modelling my “instrumented bicycle” that I rode to collect data for my Master’s thesis

I completed my B.Sc. in Environmental Science (2005) with a minor in Physical Geography at UBC. My undergraduate education exposed me to a variety of sciences, including chemistry, biology, and physics, but it was the Department of Geography that stole my heart, hence the minor because I took enough geography classes for UBC to officially recognize my affinity for the department. I loved the small classes, passionate professors, and homely permanent temporary building that never seemed to change despite all the futuristic glass and reclaimed wood structures popping up everywhere else on campus. It reflected the department that it housed: a humble and unassuming powerhouse. Geographers were kind, intelligent, and a little rough and quirky. Those classes in GIS and meteorology made me feel like I had just scratched the surface of something so much bigger, so I applied to do my M.Sc. in geography. I wanted to be part of that gritty yet brainy plaid- and fleece-wearing community. I didn’t apply anywhere else because there was nowhere else I wanted to study. I already felt at home here. Despite those cautions of putting all of your eggs in one basket, I got in. For two years, I worked under Ian McKendry and my thesis focused on air pollution along bicycle routes. It was only after I was accepted to the program that I learned he was an avid cyclist too: I saw it as another sign I was in the right place. I had a pretty awesome time collecting data by cycling around the city, my handlebars laden with scientific equipment that was worth orders of magnitude more than my bike. To me, undergrad was a taste of university, but in grad school, I could really gorge on the university experience. I loved learning how to formulate my own hypothesis and designing a study to test it out. Chasing knowledge was a lot more rewarding than sitting in a lecture hall and having it handed to me. I graduated in 2007, and was off into the real world.

Making liquid nitrogen ice cream at my first post-university job as a School Program Leader at the Calgary Science Centre

My first job after graduation wasn’t very glamorous and didn’t even need a graduate degree. I don’t even remember if it required a university education. It wasn’t the type of job you’d think someone fresh out of grad school would take, but I was moving to Calgary to follow my engineer boyfriend (now husband, so that all worked out) and didn’t want to land there unemployed, so I took the first offer, which was with the Calgary Science Centre (now snazzily branded as the Telus Spark) as a School Program Leader. At the time, I was still interested in a career in environmental education, so I figured that would help me with the education part. At first, it was a lot of fun because I was running hands-on workshops for kids coming to the science centre for school field trips and organizing summer campus. Some days I felt like I was being paid to play. I built rollercoasters using K’Nex and solar cars with Lego, I did experiments with liquid nitrogen and Bunsen burners. The first year was great and I felt it was pointing me toward my aspiration of being a “community-based environmental educator”. But when September rolled around again, I just got a sense of “Oh. Here we go again.” I was teaching the same workshops to another batch of kids. I don’t know how teachers do it year after year without feeling like a broken record. Plus, I was teaching all sorts of science, from geology to physics. I missed environmental science. It was time for a change. Lesson learned: science is cool, but my passion is environmental science.

Launching the Car2Go carsharing service at Mount Royal University, Calgary

My next job had a stronger environmental angle: I was the Sustainable Transportation Coordinator in Mount Royal University’s (MRU) Parking and Transportation Services department. I felt like I was making a difference: I organized events to promote cycling, transit and carpooling to campus, I improved the campus’ cycling infrastructure by installing more user-friendly bike racks and a bike shelter, I helped launch a carsharing service in Calgary, and I studied how people were getting to campus and why they chose the method of transportation that they did. Those were my “Transportation” duties, but I also had “Parking” duties at the customer service desk. Parking was the most hated department on campus and being at the front desk exposed me to the worst sides of both students and staff. We were sworn at and called names when parking permits were sold out or someone received a ticket. I almost cried the first time a parent yelled at me about how his daughter couldn’t buy a parking permit online, but I quickly developed a thick skin and got used to smiling and nodding and letting disgruntled customers do their thing until they calmed down. But those days were rough. Also, most of the work was project coordination and I began to miss the technical stuff like analyzing data and learning about the latest science or technology in a particular field. It was time to move on. Lesson learned: I’m a scientist at the core and I need the technical stuff to keep me entertained.

Switching from a cushy public sector job to the private industry was the most challenging leap to take yet the most interesting career change so far. I must have sent out at least 50 applications until one smallish environmental consulting company agreed to take a chance on me, someone brand new to the consulting world. My expertise was in air quality, but to start I was slotted into the regulatory group, overseeing groundwater monitoring projects. I was happy handling scientific data again and writing technical reports, but I was working with groundwater, not air. The company planned to expand its services into air sampling but I was the only person there with an air quality background. I didn’t find the guidance or mentorship that a junior staff member like me needed at this point in my career. However, it was a good introduction to consulting (hello timesheets and chargeability), and I soon found a position at a larger environmental consulting company, this time in their well-established air quality group with senior scientists who were willing to teach me the ropes. I thought it was a good fit, based on my educational background: my business card said I was an “Air Quality Scientist” and my delightfully nerdy co-workers didn’t say it looked “hazy” outside when a layer of yellow hovered over the skyline, they said it looked “NOx-y”.

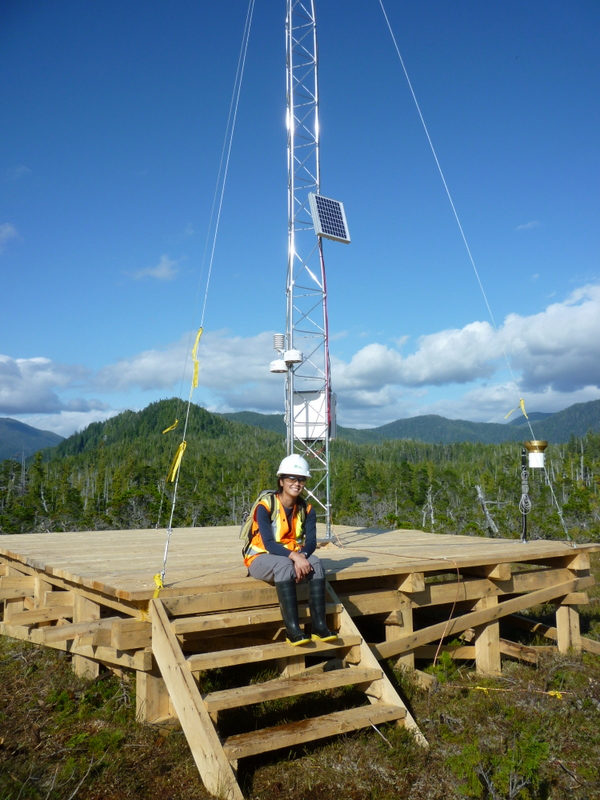

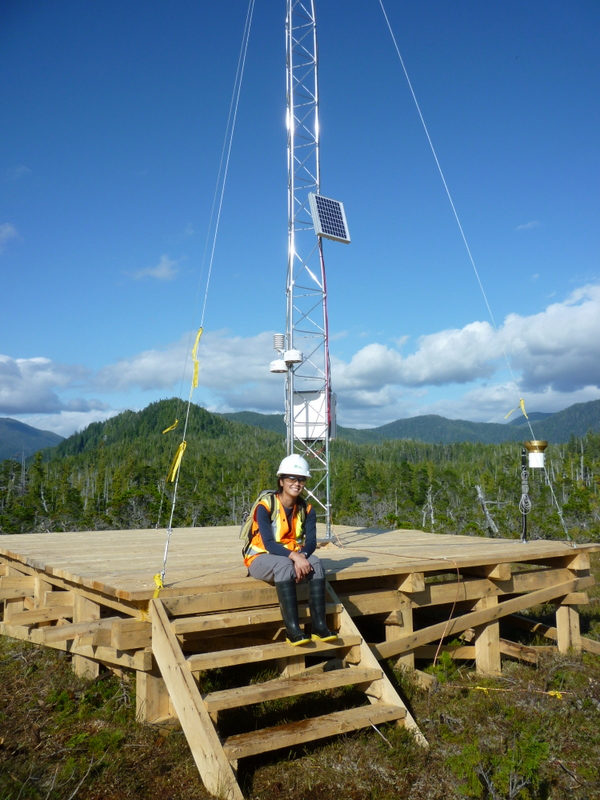

Installing a meteorological station near Prince Rupert, BC. One of the best fieldwork trips during my time in the consulting world.

I was more interested in ambient air quality, measuring the stuff that’s out there and we’re breathing in, but I soon learned most of the air-related work done in this group was dispersion modelling and emission calculations. It was too abstract for my liking. And frankly, kinda boring. No fault to the company, we just weren’t the match I thought we were. At least I was managing one field project and I had a lot more fun driving 4 hours into Alberta’s foothills to change out filters at an air sampling station than sitting at my computer trying to learn a programming language so I could run a model that would tell a client that their hypothetical facility was “clean” enough for them to pass regulators’ scrutiny. So when the recession hit Calgary and I was “reorg’d” into a contract position in a different group that did more fieldwork, I was relieved to say goodbye to the drudgery of modelling.

Fieldwork took me to many small towns throughout BC and Alberta. Often, these towns boasted having the “World’s Largest” something, like Quesnel’s gold pan and nugget.

I worked as an occupational hygienist for about a year, doing air quality monitoring for asbestos abatement, measuring noise levels, and sampling paint to test for lead. I loved the fieldwork and travelled all over Alberta and BC to places I never would have visited otherwise (like Grand Prairie, Rainbow Lake and Medicine Hat in Alberta and Campbell River, Fort St. John, Dawson Creek, Chetwynd, Prince George, Quesnel, Williams Lake, and 100-Mile House in BC), but my personal life got put on hold because it was difficult to do anything when I was being sent to the field, often for weeks at a time, on short notice, or being asked to work evenings and weekends. The travel was exciting at first, but quickly became draining. And occupational hygiene wasn’t what I went to school for. Lesson learned: consulting was an adventure but they work you like a dog and I felt disconnected from local communities. I was helping our clients succeed, but I wanted to devote my time to a more noble cause that would help everyone, not just private companies. Consulting had the technical stuff that my job at MRU was missing, but it was missing the community-based stuff that MRU had.

Suited up to go inspect an asbestos abatement project.

So when my contract ended, I felt like I had been set free. The Calgary economy was still weak, so I saw this as a chance to search for a job in a different city because I knew the job market in Calgary would be small and highly competitive. My husband and I always said we’d go where the jobs were, which was the main reason why we moved to Calgary in the first place after graduating from UBC. We’d toyed with the idea of moving back to Vancouver, so maybe now was the time.

Back to a cushy office job at Metro Vancouver. It was the first job where I had my own office… until we moved into our new building and everyone was put into cubicles.

And now here I am, back in a cushy office job, as an Environmental Technician with Metro Vancouver’s Air Quality and Climate Change group. Although my title might make it sound like the job has a lot of fieldwork, it doesn’t. I do more data management and analysis than data collection, but I also coordinate projects and write reports.

It was surprising, and a little flattering, when I showed up on my first day and a couple of my coworkers said they were familiar with my Master’s thesis, despite me completing it and being removed from the BC air quality community for the last decade. Some even asked if they could read my thesis. And I was amazed to find my research referenced in one of the technical reports used here. When I had worked in consulting, the sentiment I got from my co-workers was something like, “How cute, you have a Master’s degree. Now hurry up and get me those CALPUFF model input files.” But here, I felt respected. But it wasn’t so much those 3 letters after my name that made me feel at home: it was the connections I had forged and the work that I had done during grad school that resurfaced at Metro Vancouver, as if the air quality community was welcoming me back. And it’s a small community: if “UBC” and “air quality” appear on your resume, chances are we’re separated by fewer than six degrees. It turned out that my group at Metro Vancouver worked quite closely with Michael Brauer, who was on my thesis supervisory committee. When I was working on my thesis and needed air quality data from a Metro Vancouver (known as GVRD back then) monitoring station, I had reached out to staff at the GVRD, who I now sit a few desks away from.

I’m days away from my 3-year Metro Vancouver anniversary, and I still feel like I have a lot to learn and contribute. I don’t see an expiry date. The job has remained fresh, with a mix of projects that keep me busy and interested. I might even break the 4-year mark here, which I’ve never done at any of my previous jobs. Sure, there are days when I roll my eyes at the bureaucratic hoops I need to jump through to finish one task, and projects that languish for years without anyone making a big deal about it make me yearn for the “get ‘er done” efficiency of consulting, but the cool stuff certainly outweighs these annoyances. And isn’t that what we all hope for in a job?

The funny thing is that it feels like I’m being steered back towards my long-ago ambition of working in community-based environmental outreach: because of my knack for giving projects snappy names and my hobby of creative writing, I was assigned to lead our group’s annual public-friendly report on air quality and climate change. I write about technical topics for a non-technical audience, which I imagine is something an environmental educator might do, and working for the government is sort of like working with a really really big community. Maybe some abandoned ambitions still manifest themselves when given the chance, albeit tempered by experience and reality.

This job is like a more science-y version of community-based environmental outreach, which satisfies my nerdy side. Environmental science? Check. Technical stuff? Check. Making a difference in the world? Check. Related to what I did in school? Check. As a bonus, this job reconnected me with my UBC Geography roots: the Department of Geography found me again because I was working here and invited me to contribute to this blog, so I’ve now come full circle, from geography student to geography alumnus supposedly imparting wisdom to current geography students.

Maybe what I’m looking for in an ideal job will change again in the coming years as I develop my career, and this job will lose its lustre. Maybe it won’t. Although what I want to do for a career might change, as well as the titles on my business cards, one thing that will stay the same is that I’ll always be part of the community of UBC geographers, and proud of it.