By PhD Student, Noémie Boulanger-LaPointe

Pristine landscapes, untamed wildlife, and heroic explorers are too often the images used to represent the Canadian Arctic. Last summer, I completed my seventh field season in the Arctic and was struck more than ever by the importance of human-environment interactions, pollution, and intensive land use. Vast landscapes and wildlife encounters are nonetheless part of daily life, but human interventions cannot be ignored. While in the Department of Geography, most people describe themselves as either ‘physical’ or ‘human’ geographer, I’ve got to think of myself as a geographer, period. Working in Nunavut’s communities, where people strongly identify with the land through ancestral tradition and contemporary use, the links between human and non-human, environment, climate, and land use are tangible and as such, a fertile ground for geography investigations.

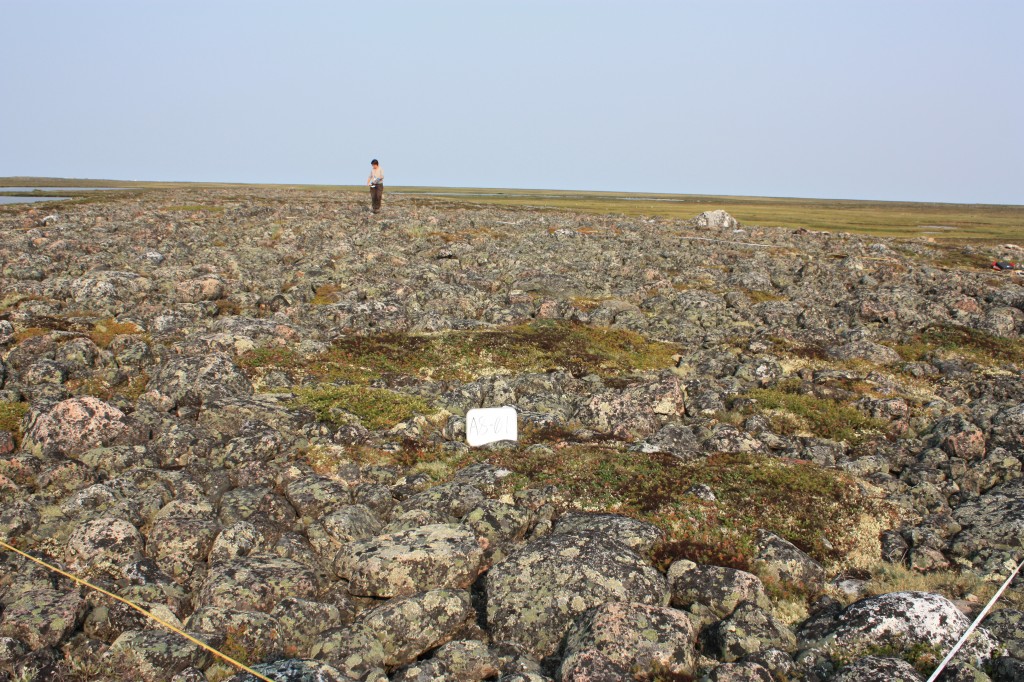

At the heart of my investigations are berries: how much berries are there, where can they be found, who eats them among humans and animals and what place do they occupy in Inuit societies? Having the chance to work with a team that has been collecting data on the field since 2008, I am consolidating and analyzing existing dataset as well as going back on the field for complementary data. Part of my work will be to create maps presenting berry productivity and animal activity across the landscape and, to analyze inter-annual variability in fruit productivity. Using data from interviews and workshops with local land users and elders, I will also document past and current berry picking sites as well as the importance of berries in every day life. The information will be combined to identify the agents in Arctic berry biocultural system. Traditional land use studies in the Arctic have largely focused on hunting practices and thus emphasize men’s knowledge of the land; studying berries gives access to women-centered knowledge and opens up different perspective on Inuit land and culture.

Working in collaboration with and giving back to the communities are intrinsic components of this project. In 2014, I met with representatives of the Department of Education in Arviat and Rankin Inlet to work on science curriculum material and develop activities on the land. I conducted activities with the high school students in Kugluktuk, including a berry mapping exercise, berry picking and plant identification on the land. I also had the opportunity to participate in a youth camp organized by Sarah Desrosiers, MSc student in Geography, but led by local elders. During the first week of September, I attended the Kivalliq Science and Culture Camp in Rankin Inlet with youth and teachers from the region. These experiences encourage me to complement my research project with an analysis of different ‘educational’ opportunities offer to youth on the land and how they may offer insights into the decolonization of education in the North.