Graduate student Emily Acheson is a medical geographer – studying the influence of climate and ecology on disease – and it’s an area of expertise we need more of.

“Medical geographers look beyond the house or the hospital or wherever people actually pick up the pathogen. We try to figure out what might have brought the pathogen there in the first place, and what it is about the climate of the area that could be encouraging that pathogen to spread.”

It sounds like an obvious perspective – diseases, the animals or plants that carry them, and the people that contract them are all interconnected, and influenced by their environment.

But for a long time, Acheson says, people have been studying these factors somewhat in isolation. Medical practitioners would look at how to treat the disease, and ecologists and geographers would look at where it had spread. They were talking to each other, but no one was really looking at how these different factors connected.

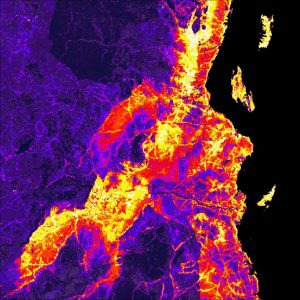

Mosquito habitat suitability in eastern Tanzania. Mapping techniques like this are central to how medical geographers understand disease. Image: Emily Acheson.

“We work a lot with GIS, geographic information systems, so the mapping is a pretty big deal. We see this in epidemiology but the ecology aspect is usually missing… We’re definitely seeing a much bigger demand for medical geographers, especially those who have training in GIS and coding.”

As what we know about pathogens and where they can be found is changing with a warming climate and the impact of human land use on habitats, medical geography may prove more essential than ever in the future.

“Now that we’re seeing climate change accelerating even at a pace that scientists didn’t predict, it’s having unprecedented effects on disease. With the permafrost and ice melting, there are pathogens frozen in that ice. So what happens when that ice melts? What happens when areas that haven’t been warm are suddenly warm?”

Sound like the plot of a horror movie?

It is. 2009’s The Thaw.

But it also became a reality in Siberia in 2016.

Another eerie blurring of pop culture and reality actually predicted Acheson’s own research, and it happened surprisingly close to home. An early episode of The X-Files, filmed on location in the North Shore mountains, explored the consequences of logging old growth forest and unleashing potentially harmful pathogens within.

Acheson’s most recent paper, and the focus of her PhD here at UBC, is an outbreak of a fungus called Cryptococcus gatii on Vancouver Island in the 1990s. In partnership with the CDC, she is looking into the cause of the outbreak, and the consequent spread of the fungus in this part of Canada.

“It was first detected in Canada on Vancouver Island. We now have between 25 and 30 cases a year [in BC]. Those aren’t necessarily fatalities, but they are cases. So it’s quite persistent but in very, very low numbers. People often panic right away when they hear about it and say ‘Oh no, am I going to get sick?’ The likelihood is small, but it’s still possible. So it’s most important for people to be educated about it.”

Cases are still extremely rare, but you can ask your doctor to test for C. gattii if you are concerned that you have any of the symptoms.

Originally seen as a ‘tropical’ organism, C. gattii had existed in California for a long time, so its appearance in Canada shocked many who perceived the country’s climate as colder.

Acheson says this is a key problem in the way we think about climate, and part of why she believes medical geography to be so essential.

“We need to acknowledge that every country has a variety of climates and a variety of climatic zones. Some people generalize across the entire country, which is usually wrong because countries are huge and often span lots of different climates.”

For the purposes of studying disease, climate is often classified by latitude, but this falls down quickly when you think about a country as large as Canada. Vancouver and Montreal share a similar latitude, with Vancouver actually slightly further north, but it has a Mediterranean-like climate that is fairly temperate year-round.

“Once you think of the climate that way, it doesn’t make the 1999 outbreak as shocking as it originally was perceived to be.”

As for the root cause of the outbreak, one theory is the deforestation linked to the construction of the Inland Island Highway just a few years before the first cases in 1999. This is what Acheson is working on next.

“The idea is, you cut down a tree, the fungus grows on the tree, and when you cut the tree down and disturb the environment you spread spores in the air, which then helps the spores spread to new locations. So we’re trying to use mapping to figure out if that’s actually the case or not.”

The X-Files episode Darkness Falls was concerned with the impact of deforestation back in 1993

One of the big future questions that medical geographers are working on is the increasing impact of human land use on disease.

“Lyme disease is a perfect example of deforestation and the effects that that can have. The more fragmented a forest is, the more forest edges you have. The more forest edges you have, the more animals who like to live on the edges are there, so their populations go up — like white footed mice and white tailed deer. Those are perfect hosts for ticks and then on top of that you have people building their houses on the edges of those forests and now you’re increasing the interaction of the hosts with potential hosts.

Anyone who studies GIS and does mapping can map that quite easily and see those effects. So we see this kind of northern expansion of ticks further and further into Canada. It’s becoming a real health emergency, especially in Ontario. So that’s actually a combination of deforestation and climate – both of which medical geographers could work on.”

You can read Acheson’s full findings in Climate Classification System–Based Determination of Temperate Climate Detection of Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato which appears in Emerging Infectious Diseases.