UBC Geography student Deanna Shrimpton and alumni Maegan Poblacion and Jim Hodgson present their alternative route for Tolkien’s characters

Set in the fictional world of Middle-Earth, J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy has inspired vigorous discussion and speculation over the years about its societies, languages and even geology.

But it took geographers to ask – did Frodo Baggins actually take the best route to bring the One Ring from the Shire to Mordor?

A team of UBC Geography students decided to tackle this question using geographic information system (GIS) techniques. Deanna Shrimpton, Maegan Poblacion and Jim Hodgson conducted a least-cost path analysis of the fellowship’s journey across Middle-Earth. This method is usually used to calculate the most suitable and cost efficient route for a client to achieve their goal – in this case the aim of destroying a magical ring and broadly avoiding death and destruction.

Mapping the unknown

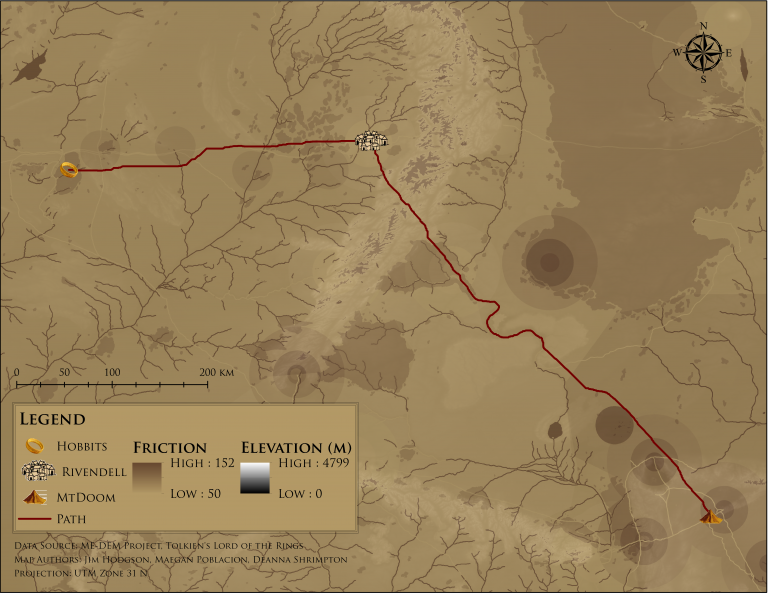

Although Tolkien provided a map of his fictional world, acquiring the necessary data to create a detailed topography of a place that doesn’t actually exist is… challenging. Luckily, the team were able to use some existing height maps and other data from the Middle-Earth DEM project to create their own digital elevation model – a 3D representation of Middle-Earth’s landscape. Working in the likely impacts of mountains, rivers, forests and weather conditions like snow on the hobbits’ progress, they then began to plot the journey.

With an ever-shifting landscape of armies, humans of questionable allegiance and Nazgul (Ringwraiths) complicating the picture, a timeline was carefully reconstructed from the books and movies to assess where and when the hobbits would have had to amend their route or pace due to social and political factors along the way.

38 days to Mordor

The result? The group found that the optimal route through Middle-Earth takes significantly less time than it did in the books – minus resting time, the party would have made it to Mount Doom in just 38 days*, rather than 3 months.

While the hobbits in the modelled journey were puzzlingly willing to summit mountains that their story counterparts did not (a quirk that the team notes may be due to the difficulty of sourcing accurate elevation data), Tolkien’s characters adhered surprisingly closely to the optimal path in their journey from Rivendell to the Dead Marshes.

The project’s version of Frodo may even have returned to the Shire in significantly better shape, as he avoids the mines of Moria, the Nazgul and the giant spider Shelob. However, that might have made for a significantly shorter and less well-known trilogy…

For a full account of how the group created their map, you can read about their journey in There And Back Again.