Northern Canada has the third largest oil and gas reserves in the world. As resource exploitation has intensified in this region over the past decade, sustainable water governance has become a highly critical and contentious issue, particularly for Indigenous communities grappling with access to safe drinking water, environmental water quality, and related livelihood and health issues. Many actors (including Indigenous communities, private companies, NGOs, and government) have recently called for the development of new models of Indigenous co-governance and stewardship for water resources. This debate has been intensified by recent legal decisions (such as the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2014 Tsilhqot’in ruling) that imply an expanded approach to Aboriginal title, and thus lend greater legal support for Indigenous environmental co-governance. Geographers can make a contribution by conducting research on the social and natural science aspects of these questions.

Professor Karen Bakker has been working on these issues with her team, which includes a number of researchers with links to the department: geographer and departmental associate Dr. Leila Harris at UBC’s Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability; new faculty member Dr. Michelle Daigle); and departmental alumnus Dr. Emma Norman, who is now the Chair of the Native Environmental Science department at Northwest Indian College.

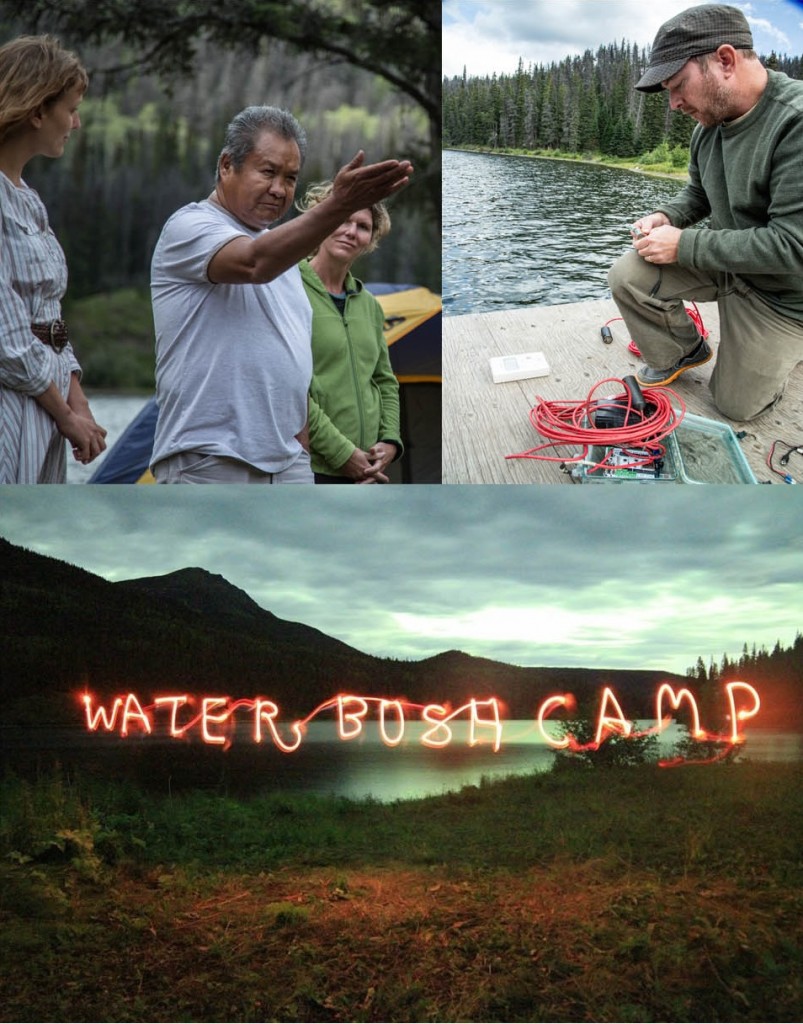

In August 2015, Professor Bakker co-organized a “Water Bush Camp,” working together with Keepers of the Water, the largest Indigenous environmental grassroots organization in Northern Canada. Held in a remote semi-wilderness location in Northeastern British Columbia, the Water Bush Camp brought together water scientists, Indigenous community members and knowledge keepers, artists and activists.

Their collective goal was to refine strategies for a major grant application to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council on “Sustainable Water Governance and Indigenous Law.” Participants learned about water monitoring, local geography and history, and toured both the Bennett Dam (the 9th largest earth fill dam in the world) and discussed the nearby controversial proposed Site C dam.

The formal welcome to the Camp is included below, and more information can be found on the workshop website: www.decolonizingwater.org.

Dr. Bakker and her team welcome expressions of interest from prospective students and potential supporters and partners of this work.

***

Funding/Donation Opportunity

Our team is applying for $2.5 Million in funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council under the Partnership Grant competition (one of Canada’s federal academic funding agencies).[1] This grant supports partnerships between academics and community partners (which can be private sector companies and/or not-for-profit organizations).

The grant requires 35% matching funds (minimum), in cash or in-kind. Potential contributions could include: field equipment (e.g. rugged tablets), travel (to fieldwork sites/destinations), backcountry training, remote sensors/monitoring devices, and environmental consulting services.

We welcome inquiries about potential partnerships: Karen.Bakker@ubc.ca

Thank you/Mussi Cho!

***

Welcome to the traditional territory of Halfway River, Saulteau, and West Moberly First Nations. You are gathered at the nexus point between Dunne-Za, Cree/Saulteau and Settler water-energy nexus issues. Surrounding you are cut-blocks, oil and gas well sites, pipelines (existing and proposed), graves, non-indigenous hunters, and recreational land users—within the context of a resurgent indigenous cultural history of this territory, one of the most productive big game regions of the world.

To the West is Klin-Se Za, the sacred twin sister mountains. To the North is WAC Bennett Dam (completed in 1967), which created the Williston Reservoir—the largest in British Columbia. To the South is the “Dokie” Wind Project, the first commercial wind project in the province. To the East is the site of the proposed Site-C dam, one of the most controversial megaprojects of our time. Three generations of your hosts have fought some of these projects; three generations of your hosts were involved in building them.

This gathering is our first Water Bush Camp: Tu k’iye kime. We come together as Indigenous community members, artists, activists, and academics in a “learning from the land” experiment in decolonizing research methodologies, replicating the experiences and traditional gathering practices of the Dunne-Za.

You were all invited intentionally as a collective committed to saving our waters, sharing our experiences, and deepening our alliances. Every one of you is here for a reason.

Throughout our time together, we will learn how we might strategize and collaborate on a new vision for water protection in this very special part of the world.

Mussi Cho.

***

By Professor Karen Bakker

Images by Zack Embree